Understanding False Positives in Drug Testing

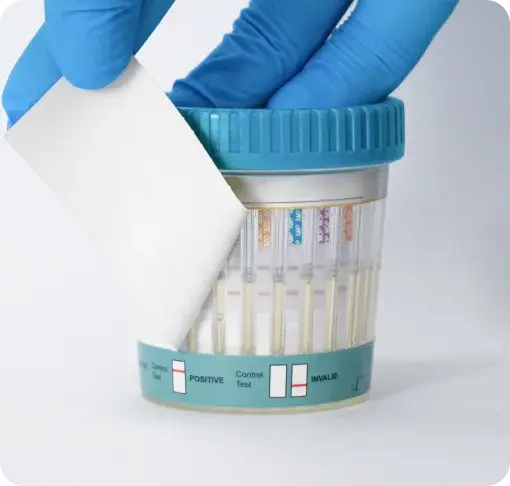

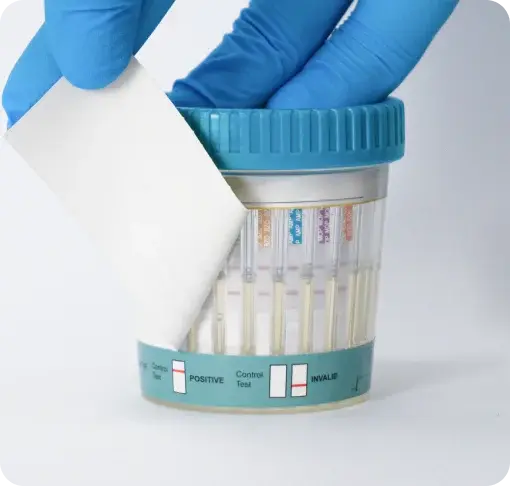

Drug testing plays a crucial role in workplaces, healthcare settings, and legal systems to ensure safety and compliance. However, despite the reliability of modern point of care drug tests, false positives can sometimes occur. False positives happen when a drug test incorrectly identifies a substance, showing a positive result when the individual hasn’t used that substance at all. Interestingly, everyday foods and common medications can sometimes trigger false positives, leading to confusion and misinterpretation of results.

In this blog, we’ll explore how substances like bananas, methadone, and CBD oil can cause false positives in drug tests and the science behind these occurrences.

Riley and the Banana False Positive

Have you ever wondered, "Can bananas cause a false positive drug test?" Well it's true, we can confirm that something as innocent as a banana can lead to a false positive for amphetamines. In a real-world case study, Riley, a participant in routine oral fluid drug screening, tested positive for amphetamines despite not using any illicit drugs. After further investigation, it was discovered that Riley had not observed the required "nil by mouth" 10 minute period before the screening and had eaten a banana.

Bananas contain high levels of dopamine, which, when consumed, can result in a chemical reaction that mimics the structures of amphetamines. Both dopamine and amphetamines share a similar chemical structure, including a benzene ring and an amine group. This structural similarity can confuse drug tests, leading them to mistakenly identify dopamine in the banana as amphetamines. This case highlights the importance of adhering to the recommended procedures before a drug test, especially the "nil by mouth" rule, to avoid such false positives.

Sam and the Ketamine False Positive

Sam, a forklift truck driver, faced a highly stressful situation when a routine point-of-care urine drug test returned a positive result for ketamine. Unbeknownst to him, the over-the-counter Benylin Dry Cough Syrup he had taken over the weekend to alleviate a persistent cough contained dextromethorphan. This ingredient, intended to suppress his symptoms, triggered a false positive for ketamine, leading to his suspension from work. Despite the initial result, a confirmatory laboratory test ultimately proved Sam had not used ketamine, allowing him to return to work.

This false positive occurred due to chemical cross-reactivity between ketamine and dextromethorphan. Both substances share structural features, such as a benzene ring and a nitrogen-based functional group, which caused the test to incorrectly detect ketamine. This highlights the critical importance of confirmatory testing to avoid unnecessary distress and ensure fairness in drug screening scenarios.

Drew and the Cannabis False Positive

Drew, who is HIV positive, experienced a false positive for cannabis during a routine urine drug screen. Despite denying cannabis use, Drew's initial result raised concerns until confirmatory testing demonstrated no trace of the substance. Further investigation revealed the cause: Drew's HIV medication, efavirenz, had cross-reacted with the cannabis test. The medication’s molecular structure inadvertently triggered the false positive result, highlighting the potential pitfalls of point-of-care drug testing.

Efavirenz and cannabis compounds share key characteristics, including hydrophobicity and a benzene ring, which can lead to misidentification in certain tests. This case reinforces the importance of laboratory confirmatory analysis in distinguishing true positives from false ones, particularly when medication use could influence initial results.