BBV Testing in Prisons: A Vital Step Toward Public Health

Bloodborne viruses (BBVs) such as Hepatitis B (HBV), Hepatitis C (HCV), and HIV pose significant public health challenges worldwide. Within the prison population, the prevalence of these viruses is particularly high due to various risk factors, including a history of intravenous drug use, unprotected sex, and limited access to healthcare prior to imprisonment. In 2014, English prisons implemented an “opt out” system of opt-out BBV testing. This has proven to be a vital step in addressing these challenges, offering critical benefits not only to inmates but also to public health at large.

The Success of Opt-Out BBV Testing in Prisons

Before the introduction of opt-out testing, the uptake of BBV testing in prisons was alarmingly low. In 2010, only 5.3% of the prison population underwent testing for these viruses, leaving a significant number of infected individuals undiagnosed and untreated (Gov.uk). The introduction of opt-out testing marked a paradigm shift, ensuring that every individual entering the prison system would be automatically tested for HBV, HCV, and HIV unless they chose to decline. This approach drastically improved the rates of testing, leading to early detection and timely intervention.

By March 2023, data from NHS England showed that 71% of individuals who accepted testing and remained in the same establishment for two weeks were provided with antibody testing within that time frame. This represents a significant improvement, especially when compared to the pre-2014 levels. While slightly below the target uptake of 75%, the progress made so far is commendable and highlights the success of the opt-out policy in expanding access to BBV testing (Gov.uk).

Early Detection Saves Lives

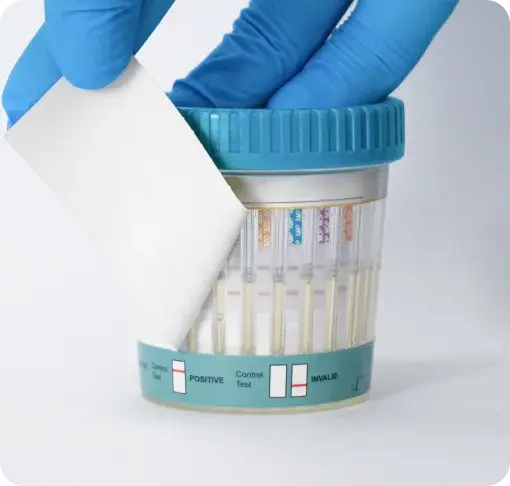

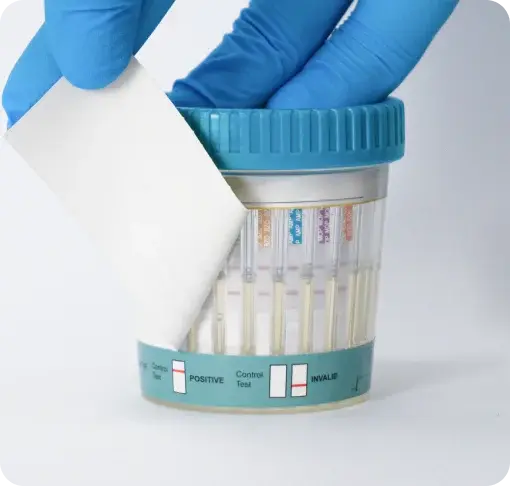

One of the key benefits of BBV testing in prisons is the early detection of infections. Many individuals entering the prison system may have been living with undiagnosed HBV, HCV, or HIV for years, potentially suffering from worsening health outcomes as a result. Early detection using rapid BBV tests allows for timely intervention, including further diagnostics and the initiation of treatment, which can significantly improve an individual's health and reduce the likelihood of virus transmission to others.

For instance, Hepatitis C, if left untreated, can lead to serious liver conditions such as cirrhosis or liver cancer. Early detection through BBV testing ensures that those infected can receive antiviral treatment, which is often highly effective in curing the infection and preventing long-term health complications. Similarly, early diagnosis of HIV allows for the initiation of antiretroviral therapy, which can suppress the virus to undetectable levels, improving the individual's quality of life and reducing the risk of transmission.

Public Health Benefits Extend Beyond the Prison Walls

The benefits of BBV testing in prisons extend beyond the individual, impacting public health more broadly. Prisons can serve as a critical point of intervention, especially for populations that might otherwise have limited access to healthcare. By identifying and treating BBVs within the prison population, the risk of transmission within the prison and upon release into the broader community is significantly reduced. This contributes to the overall effort to control and eventually eliminate these viruses as public health threats.

Moreover, prisons are unique environments where healthcare interventions can be administered systematically and at scale. The opt-out testing policy takes advantage of this setting to reach a population that is often underserved in traditional healthcare settings. By ensuring that the majority of individuals are tested upon entry, prisons play a crucial role in the broader public health strategy to combat BBVs.

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite the successes achieved since the introduction of opt-out testing, challenges remain. The current uptake rate of 71% is an improvement but still falls short of the 75% target, indicating that there is room for improvement in ensuring that more individuals undergo testing (Gov.uk). Efforts must continue to educate the prison population about the importance of BBV testing and to address any barriers that might discourage individuals from participating, such as fear, stigma, or mistrust of the healthcare system.

Additionally, ensuring continuity of care for those who test positive is essential. This includes providing access to the necessary treatments within the prison system and facilitating a smooth transition to community healthcare services upon release. Coordination between prison healthcare services and community providers is key to sustaining the health gains achieved during incarceration.

By prioritising early detection and treatment, the Criminal Justice system not only improves the health outcomes of incarcerated individuals but also contributes to the broader public health effort to control these viruses. As efforts continue to reach the target uptake and enhance continuity of care, BBV testing in prisons will remain a cornerstone of public health strategy, protecting both individual lives and community health.